We usually pray for rain in July and August. The summer months tend to be our driest months and oftentimes we toss around the word drought. Although here in the north east, that word carries a different weight than for those to the west of us.

One of the motivating factors that brought me to farming was the startling, youthful realization that human activity (myself included) has an impact on the world around us. My path led me to farming, because I wanted to take action and live the change that I wanted to see in the world. For me, this means raising food in a way that I believe contributes to health rather than diminishes it.

However, I did not realize how much the day-to-day weather is relevant to if not an obsession by the farmer. It was clear from my first few weeks working on a farm that the weather for the day made a big difference. Not just in what we planned to do or not do, but also on a longer seasonal scale, where it can have a significant impact on the farm production and the farm finances.

I have written recently about how the choice to raise our animals outside does mean we have to learn to adapt to the weather. Raising animals confined in a barn does allow the farmer to control for environmental factors. This week we had another inch of rain.

Since the beginning of July, we have had well over an inch of rain every week, with a cumulative total of 7 inches in the last five weeks. The first few weeks of rain felt like relief. Summer heat and sun allow our pastures to greedily soak up inches of rain and the grass grows like crazy.

After 4 inches of rain in just two weeks, and neighbors to our east and south getting much more than that, our pastures started to saturate. Puddles form in the low spots, tractors start to leave money tracks in the field, and the occasional venturing vehicle needs a push out of the mud.

As a child my brother and I collected every Calvin and Hobbes book ever compiled. There is a particular strip, which I love and I think sums up diversified farming:

There is treasure everywhere, and of course what is treasure to some may seem mundane. One of the beautiful things about a diversified farm is that when one animal group struggles, usually another one thrives.

In the case of our farm and the extreme rainfall in the last couple weeks, we have faced a number of challenges, particularly with the pasture raised organic chickens. However, our pasture raised pigs are absolutely loving the wet weather.

Soggy and water laden fields mean wet chickens. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve said in the last few weeks “if only we were raising ducks, we’d have some happy birds.”

We do our best to be creative and help the chickens, however we can. I thought I’d share a fun accidental management win we had this wet summer in one of the fields where our chickens are on pasture.

Another confounding feature of a wet summer is that it is very difficult to cut hay. Especially for farmers, who make “dry hay,” which means hay that is let dry to a very low moisture level (below 20%) , and then baled into dry hay bales. Some farmers cut hay and only partially dry it, then it is baled and wrapped in plastic to make a fermented product known as baleage.

Without a solid 2 to 3 days of dry weather, you cannot make dry hay in the northeast. Our plan this year was to cut hay in the field where the chickens are. We typically like to cut our first cutting of hay in June, this is because in June the grass is still green and in its vegetative state. This makes for nutritious hay for the animals who eat it and allows for productive green regrowth after the hay is cut.

However, without the weather to make hay, July came and went, and the grass just kept on growing. For a while there, Tully, Otis, and I complained that the grass was too tall. This makes it difficult to spot gaps in the coops if there’s a contour in the field. You would be surprised how small a gap a 3 week old chicken can fit through! Sometimes in their first week out in the field a few chicks venture out from underneath the coop through a gap, and if an opportunistic predator is waiting…we often do not know until we count them at processing.

However, as the rains kept coming in the fields got wetter and wetter we began to appreciate the thick thatch of grass that the coop pushes down as it moves forward. The chickens happily hop on top of the now thick matt of downed grass to peck at bugs and grass leaves. We now fondly refer to this process as “auto mulch.”

In some places, the grass is well over 4 feet tall and this acts as an incredible buffer, like a floating raft for pastured chickens. Even if there’s inches of standing water in the pasture, the chickens stay high and dry on the thatch grass.

By the end of the 24 hours, the chickens spend on that spot of grass, they have pressed it down enough that when the coop moves on, and the rains keep coming, new grass eagerly grows up through thatch, leaving a fresh new green streak behind.

The pigs, on the other hand, tend to have the opposite problem during the summer. I’ve always found it fitting that many, if not most pig breeds are named after places in the UK, which boasts a very temperate and wet climate.

One farm fact that popular culture has absolutely nailed is: pigs love mud. Oh yes, they love mud. A rainy cool summer is paradise for pasture raised pigs.

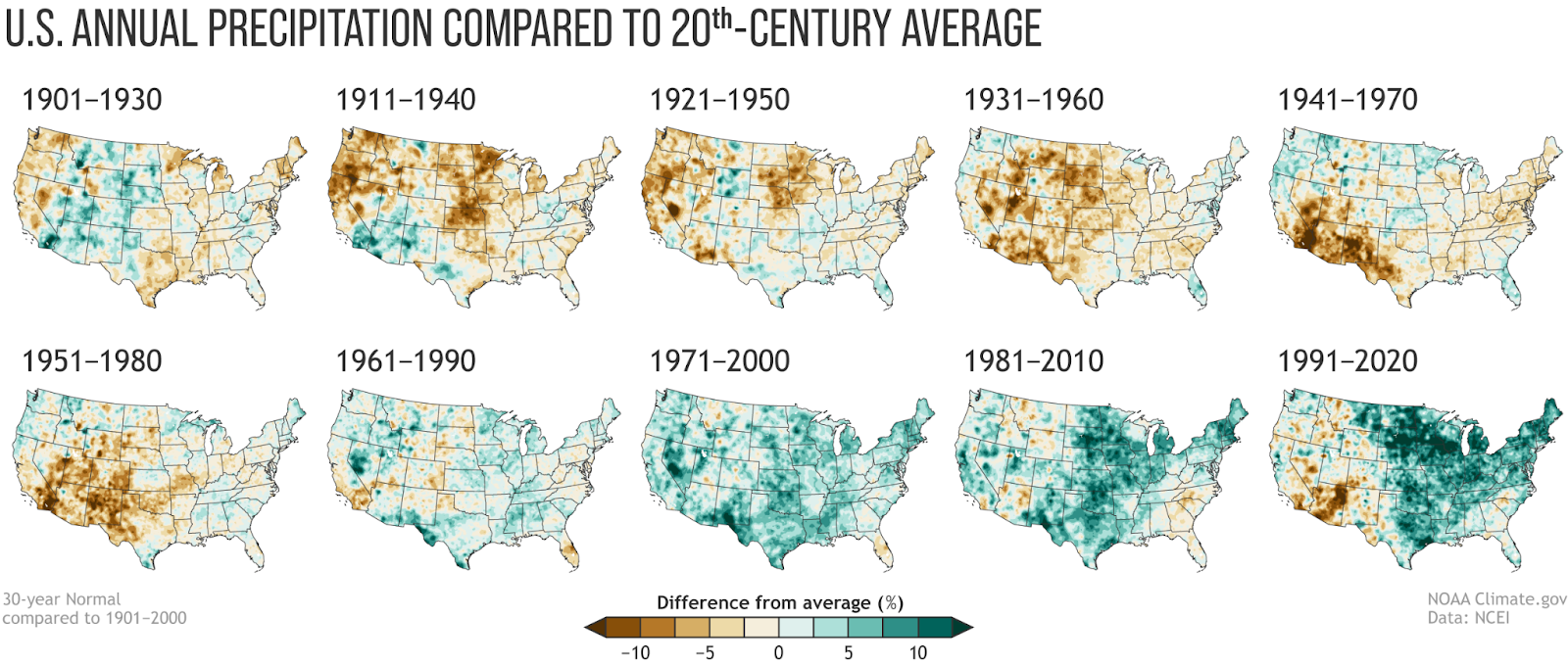

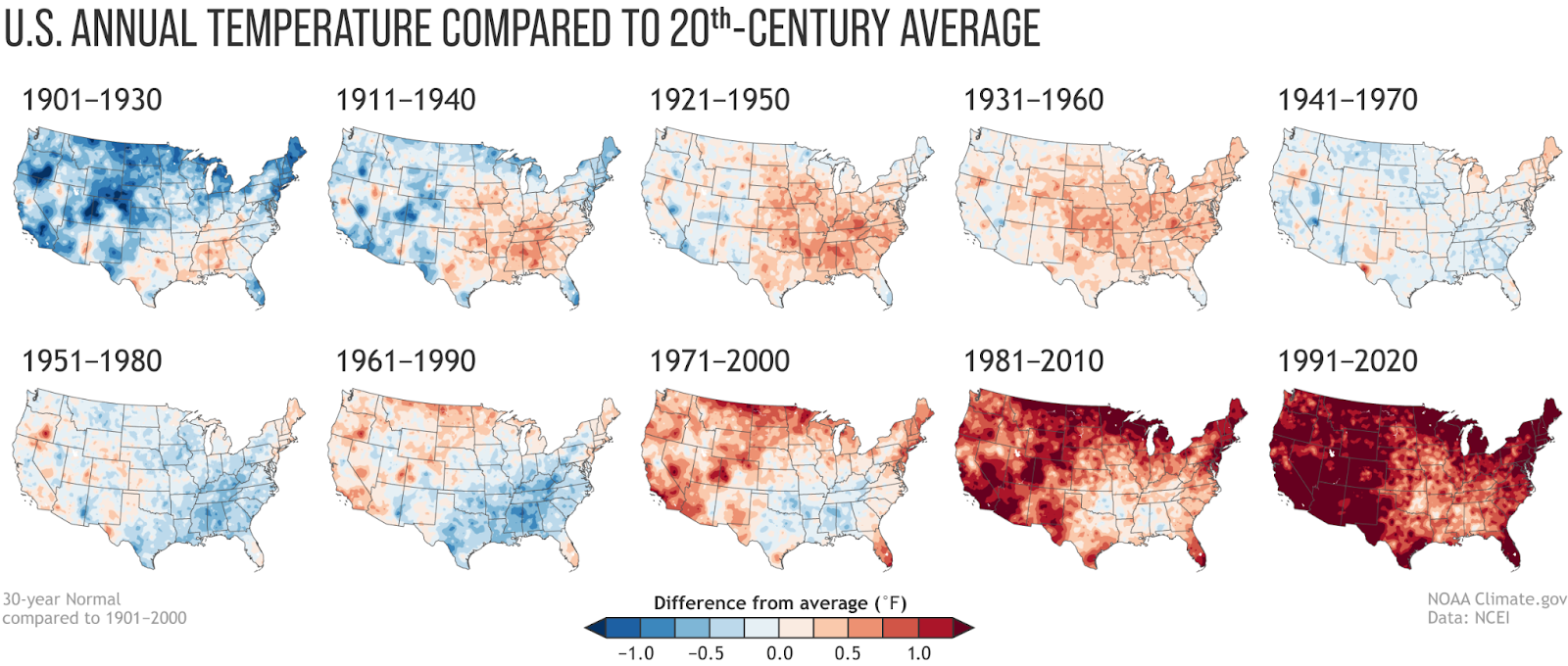

I’ll leave you with a few graphics from NOAA I found while looking at climate trends to see where this summer falls in comparison to the norm.

Enough said.